This past week, I was in Fort Lauderdale to make a commercial for work. I’m Head of Content for a Big Audio Brand and we’re kicking off a busy season of travel and shoots for summer campaigns. Our hotel was half a block from route A1A, a busy coastal highway hugged by beach and ocean on one side, and bars, restaurants, and high-rise hotels and condos on the other.

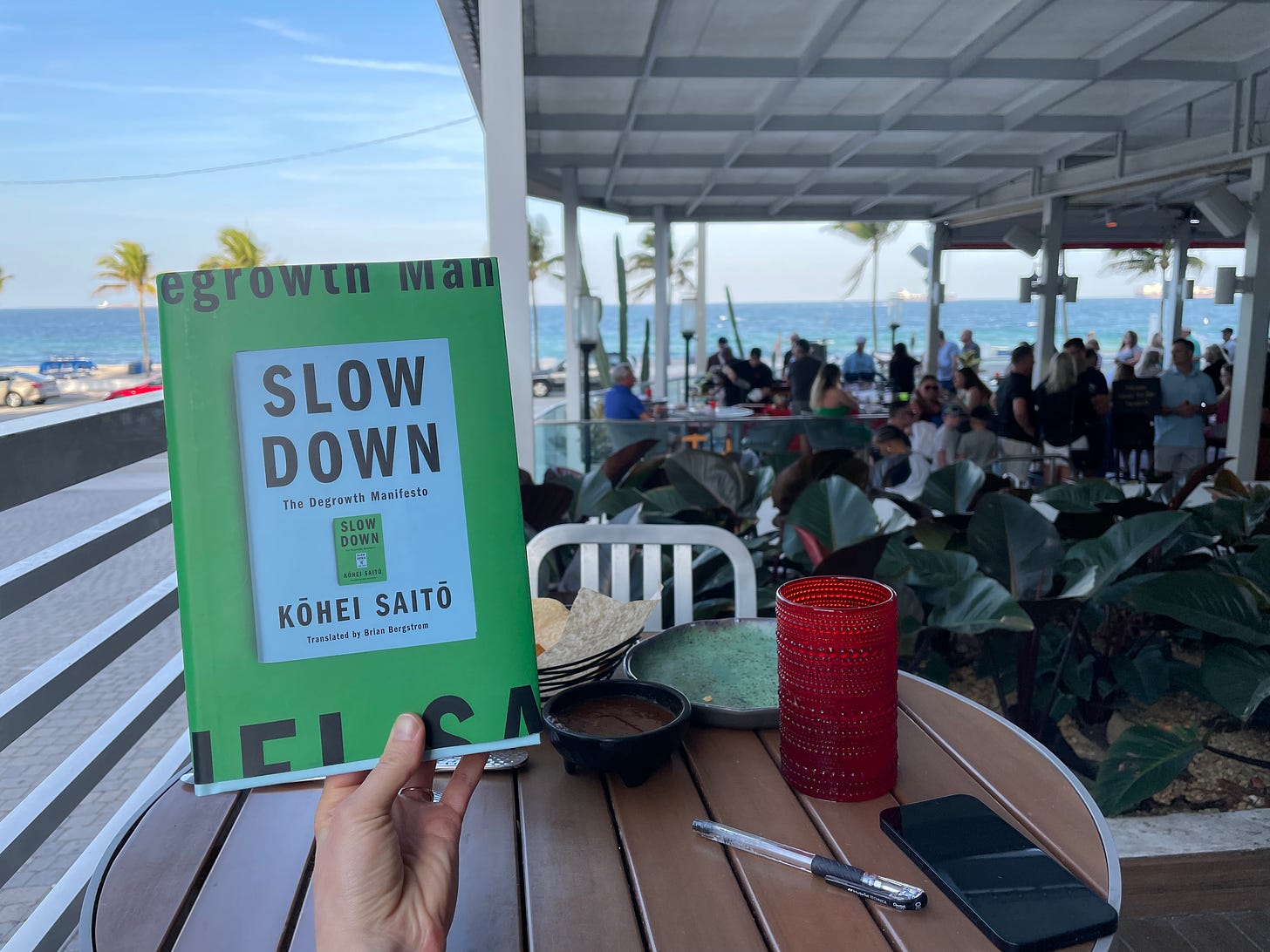

What do you see when you look at this photograph?

I grew up as a beach kid, piling into a blue Suburban with my family and driving to the beach every day in the peak of summer, camping out on the sand until the sun dipped behind us. I love the beach and I love beach life. But now, when I’m in a beach town—particularly one that shoves right up against the ocean—I don’t see a vacation.

I see a built environment that isn’t resilient to erosion, sea-level rise, and flooding. I see fewer shorebirds than in years past. And I see an increasingly privatized shoreline that isn’t accessible as a public commons for all kinds of people and families.

My first night of my work trip, I sat down for a dinner book date with our newest book club book, Slow Down by Kohei Saito, as I love to do when traveling. I looked up from Saito’s communist degrowth manifesto constantly to check work messages. And even in this scene that’s designed to help visitors drink and relax with an oceanside view, I felt anything but relaxed. It took me huge carbon emissions to fly me here and will take huge carbon emissions to fly me home. I watched the flow of alcohol, a buffet of seafood and food waste, trucks speeding by, and six container ships on the horizon, a reminder of the ship that took down the Francis Scott Key Bridge in my city just last week. The speed of consumption is off the rails.

I took a work call from my table and walked over to the ocean where the waves on my bare feet were as warm as bathwater. It’s warmer than anything we experience in the mid-Atlantic until the summer heat warms it up and October rolls around. It’s also warmer than any year on record, a sign of a rough hurricane season to come.

Heading back to my hotel, I shook off the sand from my feet, put my Tevas back on, and then proceeded to trip on a step onto the sidewalk. Dear reader, I ate it. I went down in a spectacular face plant and my book went flying.

A couple rushed over to help me up. As the woman handed over my book, she read the cover to me as a command. “Slow down!”

Right.

I hope this isn’t what our shorelines look like in 50 years. And as I write a story set in the future, I am constantly churning alternate futures through my head and deciding which one will make the more compelling story. Dystopia or utopia? Despair or hope? Obvious friction or a more subtle discontent?

My story isn’t currently set anywhere near a shoreline, but I have characters with backstories that might involve them. These fractional details of a world may matter or they may not in the final telling, but the feel important to me to understand the world I’m operating in.

World building can also be a radical act of re-imagining. If not this world, what takes its place? What future do we want to build? How can we help shape that future from here?

So, what would an alternate shoreline look like? Maybe something like this (minus the lawn):

Today, the majority of our shorelines have been hardened, a term that refers to literally hard built structures like seawalls, revetments, bulkheads and boardwalks that don’t allow for sea level rise and shoreline adaptation. Hardened shorelines erode, flood, fail.

Living shorelines of salt marsh, wetlands, and swamps, in contrast, absorb wave energy from storms and reduce their negative impact to communities farther inland. They improve water quality and foster fish habitats, oysters, and shorebirds. They’re also incredible carbon sinks, able of sequestering tons of carbon into the earth. Source

These shorelines are stronger and more resilient in their softness.

This is what makes proposals like Baltimore City’s new Inner Harbor designs so disappointing and frustrating. Instead of towering condos and asphalt pathways, I imagine a harbor filled with marshland and low-impact walkways that are designed to move or change as the weather dictates it. I imagine an area designed for play and recreation, not another outdoor mall.

Or maybe we should be designing structures built on water, like Dutch designs that have adaptation coded into their DNA.

What I’m writing

Nothing this week.

What I’m reading

Almost done with In Ascension by Martin MacInnes and my re-read of The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu.

A helpful thing

If you want to geek out about property owners transforming hardened shorelines to living shorelines, enjoy this sweet little video from the Chesapeake Bay Foundation: